Protecting coral reefs against bleaching in an ever-warming world

A Rocha Kenya has been studying coral reefs in Watamu Marine National Park (WMNP) in collaboration with Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) for the past 10 years.

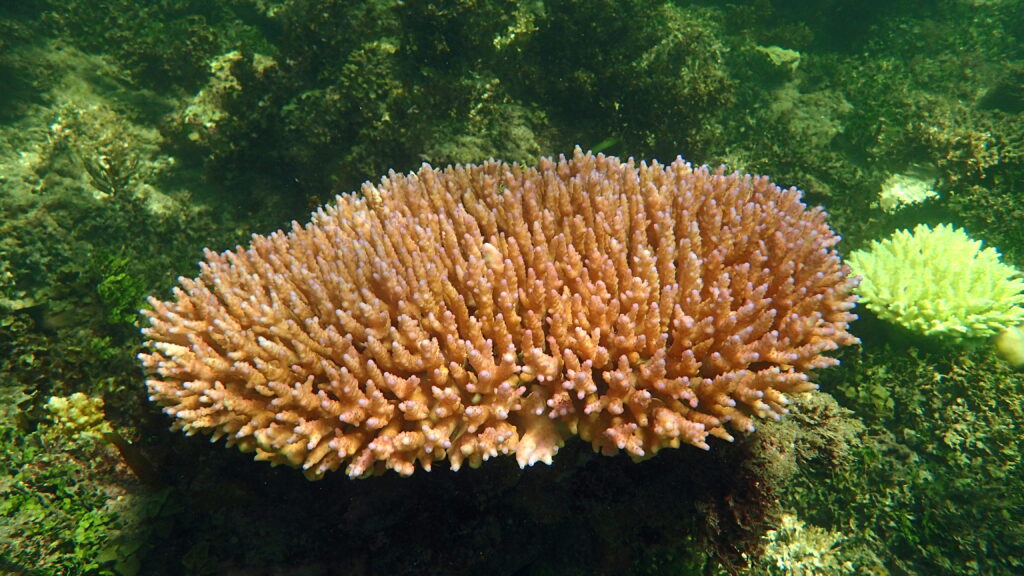

The coral reef in Watamu Marine National Park is currently experiencing its third bleaching event since 2013. (Photo: Dawn Goebbels)

The ARK marine programme has seen many young scientists gain experience in conservation and resulted in these students starting marine conservation work globally through the A Rocha family of national organizations. Dr Benjamin Cowburn, affectionately known to us as Benjo, was ARK’s first marine volunteer and intern, living at Mwamba for several years while he completed his Ph.D. at Oxford University. He pioneered our coral reef bleaching research and continues to this day to work with ARK on this and many other marine topics. Benjo writes about the current coral bleaching work in WMNP and some of his experiences over the past years.

Bleached corals take a white, or fluorescent yellow or pinkish color (Photo: Dawn Goebbels)

“Coral bleaching is the biggest threat facing coral reefs today. During abnormally hot conditions, brightly coloured corals turn bone white, are unable to feed without their symbiotic algae that gave them their colours and they eventually die because of the heat stress. Corals create the habitat that all other reef dwellers rely on, like trees in a forest, so losing corals is like a forest fire for the ecosystem.

Almost every reef in the world has experienced bleaching as of 2020, including the reefs of Watamu Marine National Park. When I first went to Watamu in 2011, I thought the reefs were the most beautiful thing in creation I had ever seen. I think I even cried in my mask a little! However, I was told by those slightly older in tooth that the reef was a shadow of its former self, never having recovered from the catastrophic bleaching in 1998. I decided to dedicate my time at A Rocha Kenya to understanding the impact of coral bleaching on reefs and what, if anything, we could do to protect them.

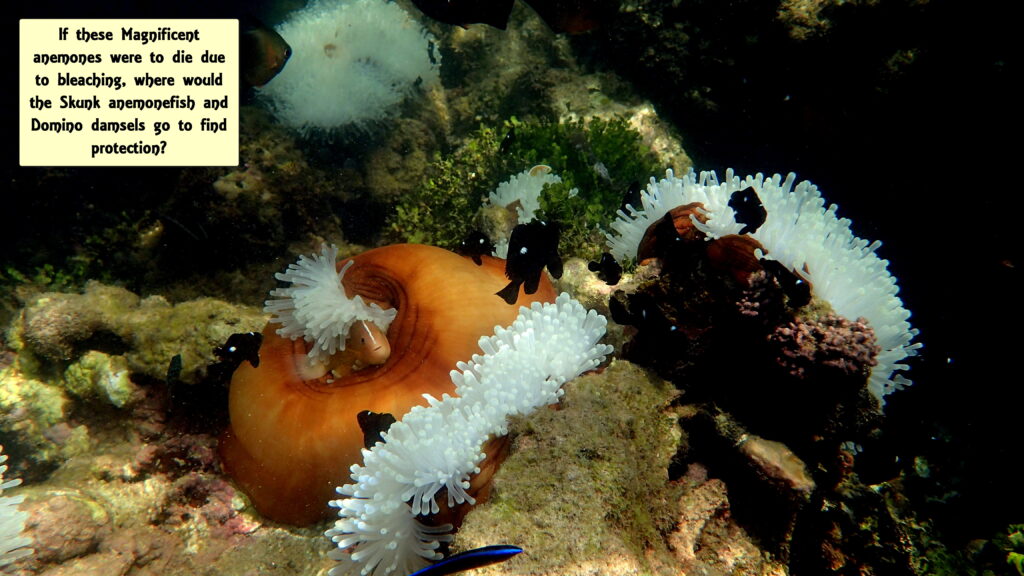

Corals create the habitat that all other reef dwellers rely on, like trees in a forest, so losing corals is like a forest fire for the ecosystem.

Forests can recover from fires and reefs can recover from bleaching, especially when protected in national parks like Watamu. However, the ecosystem needs time to recover, hence the frequency of these catastrophic events is important to the trajectory of the reef community.

Coral bleaching has chain repercussions on many reef species, including fish, crustaceans, starfish and molluscs (Photo: Dawn Goebbels)

With global climate change well underfoot, it is expected that these events will become much more common in the future, with many areas expected to get annual severe bleaching events by 2100. The A Rocha Kenya marine team recorded bleaching in 2013 and 2016, but with low levels (<10%) mortality for most corals. This gave some hope that Watamu’s corals may be adapting to better cope with heat stress, but as these events were not as hot as 1998, this was not certain. In 2020, the reefs are bleaching again and the A Rocha team, in partnership with KWS, are back out on the reef.

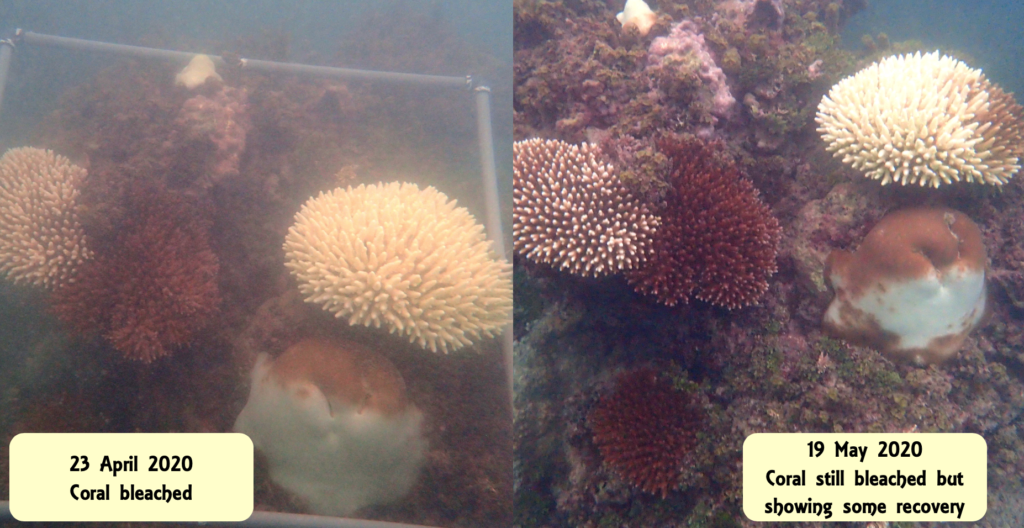

Our surveys point to hope that some corals are recovering and adapting to cope better with heat stress (Photo: Dawn Goebbels)

We use permanent quadrats, where the same patch of reef is photographed every month during the event, and the fate of each coral is observed from bleaching response to eventual mortality or survival. Through these data we are trying to ask; can these reefs survive bleaching every 3-4 years, as we’ve seen in the past decade? What changes are we seeing in the ecological community as result? What does this mean for local people who rely on the reef in Watamu?

There are many examples of colonies retaining their colour, and some that are regaining it.

The result of this current bleaching event will not be known until late 2020, but there are some hopeful signs. Overall coral cover has increased from 10% in 2011 to 20% in 2020 (before bleaching), showing that despite two bleaching events the reef recovered slowly towards its pre-1998 state with 40-50% coral cover. Also the crucially important branching Acropora or staghorn corals, which are normally very sensitive to thermal stress, are showing signs of resistance to bleaching during this event. There are many examples of colonies retaining their colour, and some that are regaining it (as of late May).

Coral bleaching affects clams and anemones as well! (Photo: Dawn Goebbels)

So might the reef become resistant?

Possibly, but there are still many colonies that are looking very unhappy and some that are starting to die. Scientists think that if we can propagate the resistant colonies that survive bleaching via ‘coral gardening’ we can help repopulate the reef with thermally tolerant corals, and give a much needed boost to this ailing ecosystem. Some think this is what is needed to get these ecosystems through the next hundred years or so until the world can get to grips with our CO2 emissions, the ultimate cause for the coral’s calamity. We will continue to collect data and share stories about this work until September when the event will be over. Let’s pray for a dramatic recovery.”

Discover more photos from our coral bleaching surveys on our social media channels this week (1-8 June 2020): @arochakenya on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter!

Indian Lionfish (Photo: Dawn Goebbels)